For over half a century, uranium has been one of the world’s most important energy minerals.

It is used almost entirely in nuclear reactors for generating electricity; a small portion of the mineral is also used in radioisotopes for medical diagnosis and research.

Nuclear power is widely considered an efficient form of energy creation. One uranium pellet weighing just 6 grams produces the same amount of energy as a tonne of coal.

Today, nuclear power is the second-largest source of low-carbon energy used to produce electricity, following hydropower. During operation, nuclear power plants produce almost no greenhouse gas emissions.

According to the IEA, the use of nuclear power has reduced carbon dioxide emissions by more than 60 gigatonnes over the past 50 years, which equals almost two years’ worth of global energy-related emissions.

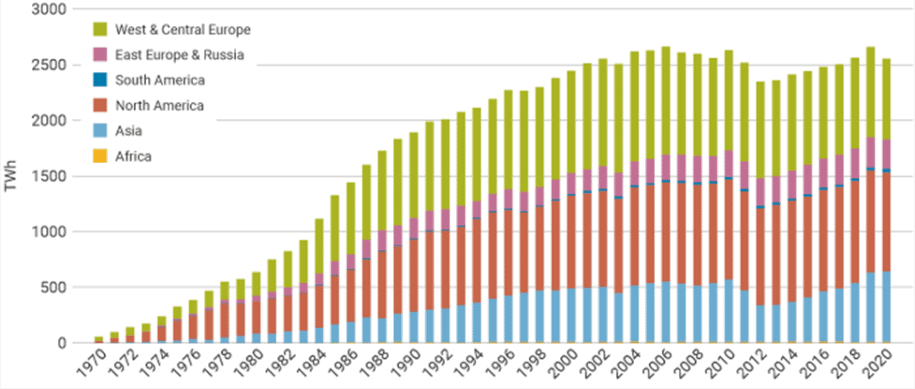

There are more than 440 nuclear power reactors currently in operation across 30 countries, with another 50 or so under construction. Together, these nuclear reactors account for around 10% of the world’s electricity and one-third of global low-carbon electricity.

As a zero-emission clean energy source, nuclear power has become a vital part of the global energy transition, which would see nations shift away from the use of fossil fuels as the main source of electricity generation.

Last year, as many as thirteen countries produced at least a quarter of their electricity from nuclear plants. Prior to 2020, electricity generation from nuclear energy had increased for seven consecutive years.

In a recently updated outlook report, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) said it expects world nuclear generating capacity to double to 792 gigawatts (net electrical) by 2050 from 393 GW(e) last year.

This was about 10% higher than the 715 GW(e) projection previously given by the IAEA, citing that many countries are considering the introduction of nuclear power to boost reliable and clean energy production.

“The new IAEA projections show that nuclear power will continue to play an indispensable role in low carbon energy production,” IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi stated.

The prospects for nuclear power will likely grow higher in the next two decades and beyond with many countries now targeting net-zero carbon emission. Growth is projected at around 2.6% annually through 2040, according to the World Nuclear Association (WNA).

Uranium Market

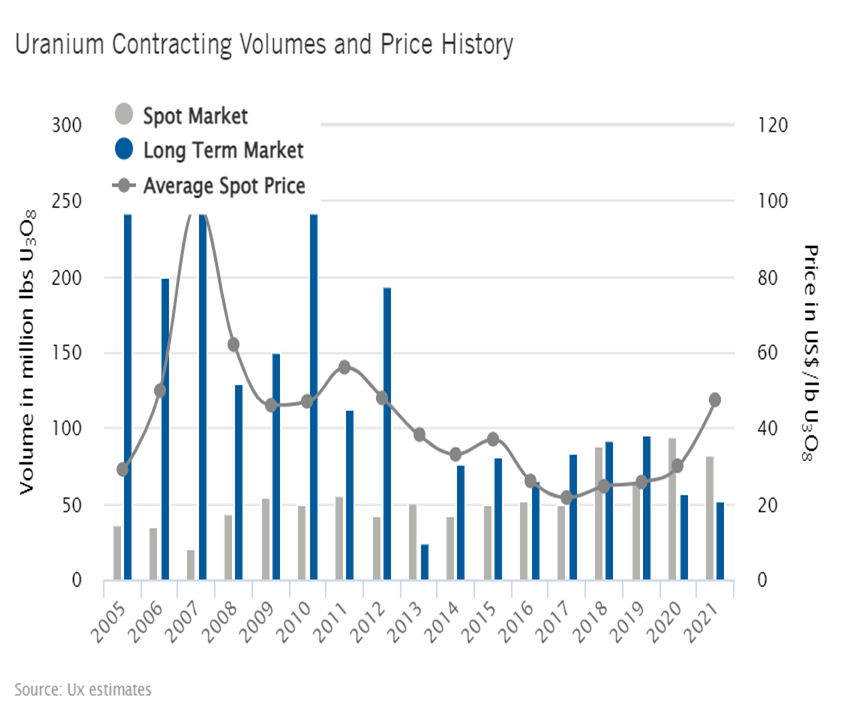

Positive developments for nuclear energy have also served as a strong tailwind for the long-dormant global uranium market.

As all commodity markets tend to be cyclical, uranium has languished near historical lows for the better part of the last decade, but the tide is beginning to turn.

Since the third quarter of 2021, uranium prices have enjoyed a sudden revival, rising by about 40% just in September, outpacing all other major commodities.

The price surge coincided with a burst of demand in uranium investments, led by Sprott Physical Uranium Trust, which has amassed a uranium stockpile that is equal to about 16% of the annual consumption from the world’s nuclear reactors, reflecting a massive bet on nuclear’s rising prominence in a carbon-free future.

Since mid-August, the Sprott fund has been snapping up uranium from the spot market almost on a daily basis, sometimes buying more than 500,000 pounds in a single day, according to its website and social media account. That helped to drive uranium futures to its highest since 2012.

Two exchange-traded funds focused on uranium — NorthShore Global Uranium Mining ETF (URNM) and the Global X Uranium ETF (URA) — have also seen a resurgence, with investors having poured more than $1 billion into them so far this year.

However, even before the recent price rally started, demand for uranium from the investment sector was growing, claims John Ciampaglia, CEO of Sprott Asset Management, which oversees the physical trust.

ETFs that track uranium are some of the best performers of the last two years, reversing a downturn that came when investors shunned the commodity following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011.

About 20 million pounds of uranium had already been locked up by buying from London investment firm Yellow Cake Plc, Toronto-based Uranium Participation Corp. and a few junior uranium development companies, according to Jonathan Hinze, president of UxC LLC, a leading nuclear fuel market research firm.

The Sprott uranium fund was formed out of an April takeover of UPC, which at the time held 18 million pounds of uranium. In March, Yellow Cake bought $100 million worth of uranium from Kazatomprom, the world’s top uranium miner. The Kazakh producer is also said to be in talks to supply uranium directly to Sprott, according to Bloomberg reports.

Although uranium demand from utilities has not increased much, Kazatomprom has warned of supply shortages in the long term as investors scoop up physical inventory and new mines aren’t starting quickly enough.

Years of persistently low prices have led to planned supply curtailments of existing production capacity, lack of investment in new capacity, and the end of reserve life for some mines. These factors are all likely to jeopardize the long-term security of uranium supply faced with a rising demand for carbon-free electricity.

To complicate matters, utilities normally do not come to the market when they need uranium; instead, the mineral must be purchased years in advance to allow time for a number of processing steps before it arrives at the power plant.

So as the spot market continues to thin, driven by investor purchases, there may not be enough uranium to adequately satisfy the growing backlog of long-term demand.

Not Enough Supply

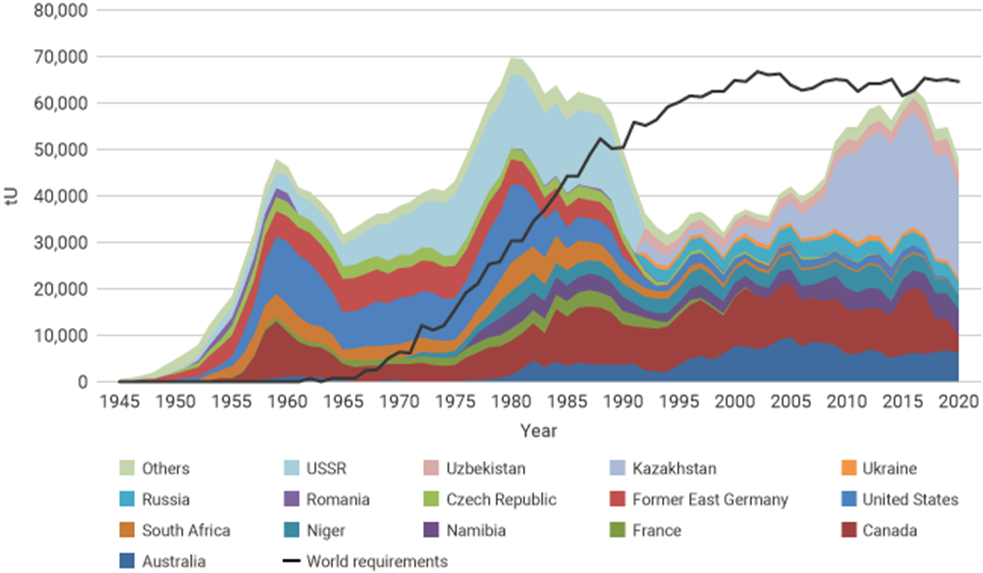

According to the World Nuclear Association, for about 445 reactors with a combined capacity of over 390 GWe, this would require some 76,000 tonnes of uranium oxide concentrate containing 64,500 tonnes of uranium from mines each year. For context, total production from mines was about 47,700 tonnes last year.

More significantly, mine production as a percentage of world demand has been on the decline for the past five years, from 98% in 2015 to just 74% in 2020, WNA data shows.

While the balance is usually made up from secondary sources including stockpiled uranium held by utilities, recycled or re-enriched uranium, and ex-military weapons, their share of the total supply will decline over time and should not be counted on for electricity generation in the long term.

According to a report by WNA, primary uranium production from existing mines will decrease by 30% in 2035 due to resource depletion and mine closures, while new planned mines will only compensate for exhausted mine capacities.

With mine output seeing further declines due to the Covid-19 pandemic and now investors hoarding more physical uranium, the industry is in dire need of strategic investments on mine projects to assuage future supply concerns.

Uranium Mining Overview

Uranium is a naturally occurring element with an average concentration of 2.8 parts per million (ppm) in the Earth’s crust. Traces of it occur almost everywhere.

In fact, it is more abundant than gold, silver or mercury, about the same as tin, and slightly less abundant than cobalt, lead or molybdenum. Large amounts of uranium also occur in the world’s oceans, but in very low concentrations.

To make nuclear fuel from uranium ore, the uranium is first extracted from the rock, then enriched with the uranium-235 isotope, before being made into pellets that are loaded into assemblies of nuclear fuel rods. In a nuclear reactor, there are several hundred fuel assemblies containing thousands of small pellets of uranium oxide in the reactor core.

The nuclear chain reaction that creates energy starts when U-235 splits or “fissions”, which produces a lot of heat in a controlled environment.

Most of the ore deposits supporting today’s biggest uranium mines have average grades in excess of 0.10% of uranium (or 1,000 ppm), and even the low-grade ores must be 0.02% to support a mine. Therefore, uranium operations are constrained to just a few places with suitable orebodies that can be mined economically.

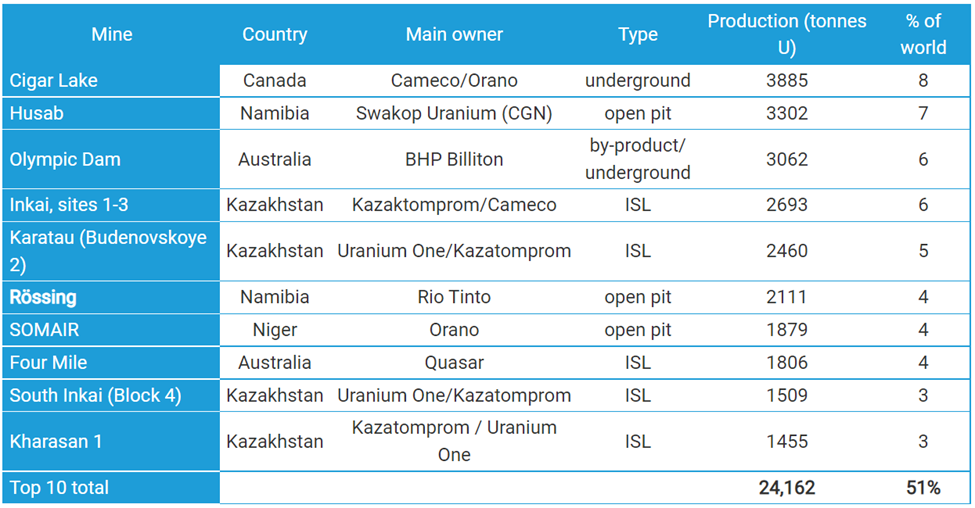

While uranium production occurs in 20 countries, more than half of the world’s total output comes from just 10 mines in five countries, with Kazakhstan leading the way as usual (over 19,400 tonnes). Other notable producers include Australia, Namibia and Canada.

Some uranium is also recovered as a byproduct with copper, as at the Olympic Dam mine in Australia (BHP), or as byproduct from the treatment of other ores, such as the gold-bearing ores of South Africa, or from phosphate deposits in places like Morocco and Florida. In these cases, the concentration of uranium may be as low as a tenth of that in orebodies mined primarily for their uranium content.

Various types of uranium mines can be found throughout the world. Open-pit mining occurs where orebodies lie close to the surface, while underground mining methods are employed where orebodies are deeper.

Meanwhile, some orebodies may lie in groundwater in porous unconsolidated material (such as gravel or sand), and may be accessed simply by dissolving the uranium and pumping it out; this method is known as in situ leaching (or in situ recovery in North America). For some ore, usually those with very low-grade (below 0.1%U), it is treated by heap leaching, which is similar to in situ mining.

Canada’s Athabasca Basin

As one of the leading uranium producers, Canada is rich in uranium resources and has a long history of exploration, mining and generation of nuclear power. Up until 2019, it had mined more uranium than any other country (539,773 tU) in history, about one-fifth of the world total.

By 2021, Canada has known uranium resources totalling 606,600 tonnes U3O8 (514,400 tU), with exploration still continuing. A majority of these resources are in high-grade deposits, some one hundred times the world average.

Canada’s uranium mining industry is represented by the major discoveries in the Athabasca Basin of northern Saskatchewan, which have accounted for most of the country’s production since the 1970s. The region is known to host some of the largest high-grade uranium deposits in the world.

The McArthur River and Cigar Lake mines, jointly owned by Cameco and Orano, have been the two main producers.

Cigar Lake is currently the world’s highest-grade uranium mine with 97,550 tonnes U3O8 (82,720 tU) of proven and probable reserves. The McArthur River mine, an even bigger operation than Cigar Lake, was placed on care and maintenance in 2018 due to market weakness.

Past production can also be found at the nearby McClean Lake operation, which in the last 10 years has mostly been used to process ore from Cigar Lake; and the Rabbit Lake deposit, most of which had already been mined out after more than 40 years of mining.

To this day, the northern part of Saskatchewan remains a world leader in uranium production, with several proposed mines waiting in the pipeline (i.e. Denison’s Wheeler River) and various projects in the advanced-exploration phase.

Marvel Discovery

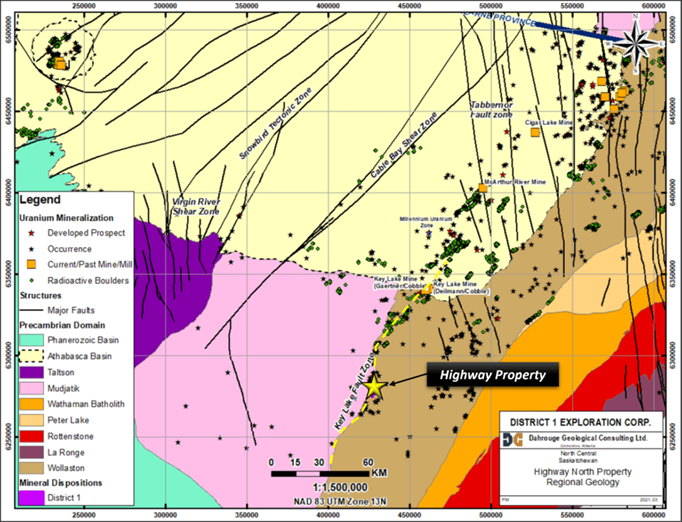

The most recent development in Saskatchewan’s uranium industry involves Canadian-based emerging resource company Marvel Discovery Corp. (TSXV: MARV) (Frankfurt: O4T1) (MARVF: OTCQB) and its latest asset acquisition from District 1 Exploration Corp.

Last week, the company announced it will assume all obligations under District 1’s option agreement to acquire a 100% interest in the Highway North property located in the Athabasca region of Saskatchewan.

The Highway North property is located 70 km southwest of the former producing Key Lake uranium mine. Aptly named for its location along Highway 914, the property consists of five contiguous claims totaling 2,573 hectares.

The Key Lake deposit, which is northeast of the property, contains two mineralized zones that historically produced a total of 4.2 million tonnes of product at an average grade of 2.1% U3O8.

Only 21 drill holes have been drilled on the property thus far totaling 3,527m between 1980 and 2008. Surface exploration and drilling have verified the presence of uranium mineralization along the Highway zone, with grades up to 2.31% U3O8 over 0.29 m.

Regional Geology

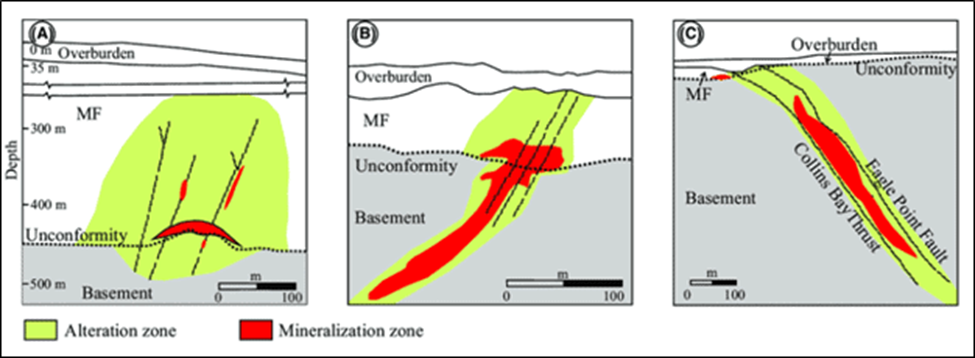

The deposit model for exploration on the Highway North property is a basement-type unconformity-related uranium deposit, such as those found at Eagle Point (part of Rabbit Lake), Millennium, and Gaertner and Deilmann (Key Lake).

This deposit type belongs to the class of uranium deposits where mineralization is spatially associated with unconformities that separate Proterozoic conglomeratic sandstone basins and metamorphosed basement rocks. Although rocks of the Athabasca Group and the basal unconformity do not outcrop on the property, they likely once overlaid the basement gneisses and metapelites which now do, as the current erosional edge of the Athabasca Basin, and potential outliers, is about 50 km north of the property.

In Saskatchewan, uranium deposits have been discovered at, above and up to 300 m below the Athabasca Group unconformity within basement rocks. Mineralization can occur hundreds of meters into the basement or can be up to 100 m above in Athabasca Group sandstone.

Typically, uranium is present as uraninite/pitchblende that occurs as veins and semi-massive to massive replacement bodies. Mineralization is also spatially associated with steeply dipping graphitic basement structures and may have been remobilized during successive structural reactivation events.

Such structures can be important fluid pathways as well as structural or chemical traps for mineralization as reactivation events have likely introduced further uranium into mineralized zones and provided a means for remobilization (see below).

The Highway Property straddles the Key Lake fault zone, an important corridor for structurally controlled Athabasca Basin-type uranium deposits.

Critical criteria on the property for these types of uranium deposits include the presence of graphitic EM conductors within metasedimentary packages, major reactivated northeast-trending fault systems that have been disrupted by obliquely cross-cutting subsidiary structures and the presence of uranium-enriched source rocks (see figure below). Exploration to date on the property has been limited.

Commenting on the company’s latest acquisition, Marvel’s president and CEO Karim Rayani, said:

“The Highway North project is perfectly situated along the Key Lake shear zone with power, water and road accessibility. The geological setting is prospective for structurally controlled basement-hosted uranium deposits such as the Millennium zone and Key Lake deposits of Cameco. Marvel continues to present stakeholders a rare opportunity having exposure to multi-commodity – critical element opportunities under one umbrella.”

Conclusion

The Highway North property adds to the company’s diverse portfolio of Canadian exploration projects that already includes gold, silver, copper and rare earth elements.

In an interview with Proactive Investors to discuss the new deal, CEO Rayani said this uranium asset acquisition may have taken investors by surprise, but in a good way. “We’ve always been a multi-commodity play, so we felt it made a lot of sense to add this to the Marvel portfolio of projects.”

The Highway North project, which was put together by an ex-Rio Tinto team, shares similar characteristics to the largest development-stage uranium project in Canada being developed by NexGen Energy, the chief executive says.

According to Rayani, Marvel is headed towards more of a “mine bank”, having already completed one spinout over the last few months, and the uranium asset may follow the same path.

“Really, we’re leveraging our shareholder base, creating share dividends and an opportunity. So we’re going against the grains as a typical mining company with gold, especially with our market cap,” he added.

With an increasing focus on nuclear power as a reliable fossil fuel replacement, it is expected that uranium exploration in Saskatchewan will continue to thrive given the province’s vast resources. A recovery in uranium prices would also stimulate a fresh wave of investments from key players in the mining industry.

With uranium prices doing well at the moment, Rayani believes that Marvel’s new uranium property, as well as its gold projects, should pick up more steam heading into 2022.